On July 4, 1939, Lou Gehrig said: “Today, I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth”-NY Times, Richard Sandomir

“This summer I got a bad break. The doctors said I couldn’t play baseball. All right. I’m still the luckiest man on earth when you add things up. I’ve still got a long season of life to play out, and my team — America — is absolutely the best in the league. That’s what counts.” Lou Gehrig, Baseball Reference, Yankee first baseman 1923-1939, including 7 World Series. Born 1903, died 1941. Image of Gehrig in Yankee cap from Baseball Reference

7/3/19, “Eighty Years On, Lou Gehrig’s Words Reverberate," NY Times, Richard Sandomir

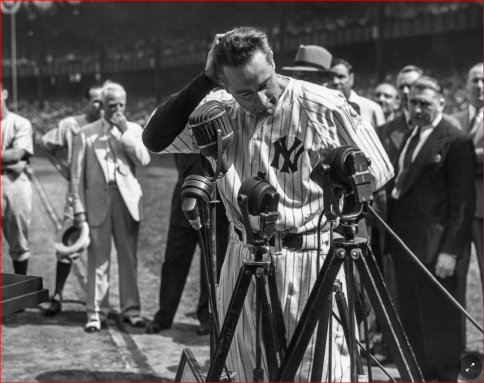

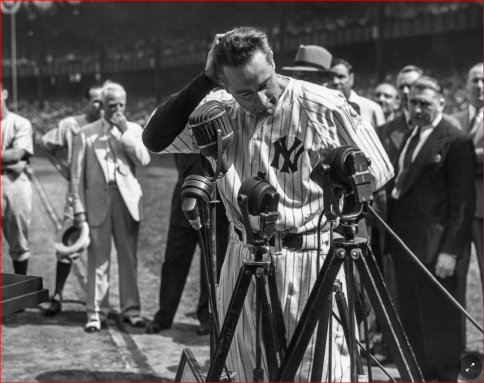

[Image] “ Credit Stanley Weston/Getty Images” via NY Times

[Image: 7/4/1939, Screen shot of crowd at Yankee Stadium cheer Lou Gehrig, MLB]

But Gehrig relented as fans chanted, “We want Lou!”

Indeed, there was nothing silly about a 36-year-old man of remarkable achievements being forced to retire from baseball because of the then-little-known disease called amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and telling the world:

“Today, I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth.”

Gehrig’s performance as a speaker that day was as remarkable as any he had as a player. And it was quite a career: a batting average of .340, 493 home runs, 1,995 runs batted in and a lifetime O.P.S. of 1.080, third in major league history to Babe Ruth and Ted Williams. He had played in 2,130 consecutive games until his finale on April 30, 1939 — when he acknowledged that his once-mighty body had betrayed him with unyielding cruelty.

So he stood, wobbly enough that Manager Joe McCarthy worried he might fall, in the summer heat between games of a doubleheader between the Yankees and Washington Senators.

Gehrig looked lonely, even desolate, a solo figure on the infield, surrounded by retired teammates from the 1927 Yankees and members of the current team who had carried on brilliantly without him, with Babe Dahlgren now at first base. They were 51-17, on their way to a 106-45 record and a sweep of the Cincinnati Reds in the World Series.

It was Joe DiMaggio’s team now.

For about an hour, though, the focus returned to the star of Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day. Gifts were presented. Speeches were made by McCarthy; the mayor of New York, Fiorello LaGuardia; and Postmaster General James Farley.

All the while, Gehrig waited, the guest of honor at a living funeral.

After some encouraging words whispered by McCarthy, who adored Gehrig, Lou reluctantly stepped to the microphones.

When that moment was described by the screenwriters Herman Mankiewicz and Jo Swerling nearly three years later in their script for “The Pride of the Yankees,” they wrote: “The roar of the crowd is like a sustained note from a mighty organ. Lou waits for it to subside but it doesn’t. For him, this is crucifixion as well as triumph, because he knows he’ll have to die twice and perhaps the worst ordeal for him is that little death known as Goodbye.”

If Mankiewicz and Swerling’s words struck a hyperbolic chord, Gehrig’s did not. They were filled with gratitude for the people in his life: Eleanor, his parents, his mother-in-law, his Yankee managers, his roommate Bill Dickey, the New York Giants and the stadium’s groundskeepers.

Both versions of the speech, the real and imagined, raise one question: What would make a man who had received a diagnosis of a terrible disease speak only of good fortune and the people he was grateful for?

Gehrig offered some perspective later that year after he had begun working as a member of New York City’s Parole Commission. With his condition rapidly deteriorating, Gehrig put his name to a syndicated article (almost certainly ghostwritten) that explained what he felt was a lifetime of thankfulness: for his parents, for making his high school football team, for attending college, for signing with the Yankees, for Eleanor.

In words that echoed the speech, he wrote, “This summer I got a bad break. The doctors said I couldn’t play baseball. All right. I’m still the luckiest man on earth when you add things up. I’ve still got a long season of life to play out, and my team — America — is absolutely the best in the league. That’s what counts.”

That season of life was all too short. Gehrig died on June 2, 1941.”

“Richard Sandomir is the author of “The Pride of the Yankees: Lou Gehrig, Gary Cooper and the Making of A Classic.”

Richard Sandomir is an obituaries writer. He previously wrote about sports media and sports business. He is also the author of several books, including “The Pride of the Yankees: Lou Gehrig, Gary Cooper and the Making of a Classic.” @RichSandomir”

.............

Tweet

Stumbleupon StumbleUpon

7/3/19, “Eighty Years On, Lou Gehrig’s Words Reverberate," NY Times, Richard Sandomir

[Image] “ Credit Stanley Weston/Getty Images” via NY Times

“Lou Gehrig had finally made it to the Yankees’ clubhouse that afternoon, drained and drenched with perspiration, having delivered a speech of such simple eloquence that it would one day be called baseball’s Gettysburg Address.

Lou had wept as he spoke — as did many of the nearly 62,000 other people in Yankee Stadium on that Fourth of July 80 years ago. Back in the comfort of the clubhouse with teammates and friendly reporters around him, he asked, “Did my speech sound silly?” It was a humble man’s question with an easy answer: it did not.

Much of the speech no longer exists as an intact recording; poor preservation of newsreels has left only four known surviving lines.

The opener — “For the past two weeks, you’ve been reading about a bad break” — leads into the “luckiest man” declaration, which was shifted to the end of “The Pride of the Yankees,” the 1942 film about Gehrig, starring Gary Cooper, for dramatic impact. In another extant sentence, he refers to his 1939 teammates as “fine-looking men” who are “standing in uniform in the ballpark today.” And his last line also survived: “And I might have given a bad break but I’ve got an awful lot to live for.”

If we think we know a complete speech, it is because of the version that Cooper delivered in “Pride,” which borrowed from what Gehrig’s wife, Eleanor, remembered of July 4, 1939, and from newsreels that had not yet wasted away or been discarded. Cooper had morphed into Gehrig, not because he looked like him or could play baseball like him, but because he knew so well how to play men of quiet dignity.

Although there had been no public announcement that he would speak, Gehrig planned some remarks with Eleanor. But he walked — in an uncertain gait — onto the field without a piece of paper. Whether he had left his speech at home or in his locker remains a mystery. If there had been a written speech, it is surprising that Eleanor had not pasted it into one of the scrapbooks she had meticulously filled to record his career and their precious few years together.

During the ceremony Lou stood with his arms in front of him, clutching his cap. His head was often bowed. By the time he was asked to speak, he made a gesture to the M.C., the sportswriter Sid Mercer, that he would not say a word. Emotion had overcome him. “I shall not ask him to speak,” Mercer said to the crowd. “I do not believe that I should.”

Lou had wept as he spoke — as did many of the nearly 62,000 other people in Yankee Stadium on that Fourth of July 80 years ago. Back in the comfort of the clubhouse with teammates and friendly reporters around him, he asked, “Did my speech sound silly?” It was a humble man’s question with an easy answer: it did not.

Much of the speech no longer exists as an intact recording; poor preservation of newsreels has left only four known surviving lines.

The opener — “For the past two weeks, you’ve been reading about a bad break” — leads into the “luckiest man” declaration, which was shifted to the end of “The Pride of the Yankees,” the 1942 film about Gehrig, starring Gary Cooper, for dramatic impact. In another extant sentence, he refers to his 1939 teammates as “fine-looking men” who are “standing in uniform in the ballpark today.” And his last line also survived: “And I might have given a bad break but I’ve got an awful lot to live for.”

If we think we know a complete speech, it is because of the version that Cooper delivered in “Pride,” which borrowed from what Gehrig’s wife, Eleanor, remembered of July 4, 1939, and from newsreels that had not yet wasted away or been discarded. Cooper had morphed into Gehrig, not because he looked like him or could play baseball like him, but because he knew so well how to play men of quiet dignity.

Although there had been no public announcement that he would speak, Gehrig planned some remarks with Eleanor. But he walked — in an uncertain gait — onto the field without a piece of paper. Whether he had left his speech at home or in his locker remains a mystery. If there had been a written speech, it is surprising that Eleanor had not pasted it into one of the scrapbooks she had meticulously filled to record his career and their precious few years together.

During the ceremony Lou stood with his arms in front of him, clutching his cap. His head was often bowed. By the time he was asked to speak, he made a gesture to the M.C., the sportswriter Sid Mercer, that he would not say a word. Emotion had overcome him. “I shall not ask him to speak,” Mercer said to the crowd. “I do not believe that I should.”

[Image: 7/4/1939, Screen shot of crowd at Yankee Stadium cheer Lou Gehrig, MLB]

But Gehrig relented as fans chanted, “We want Lou!”

Indeed, there was nothing silly about a 36-year-old man of remarkable achievements being forced to retire from baseball because of the then-little-known disease called amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and telling the world:

“Today, I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth.”

Gehrig’s performance as a speaker that day was as remarkable as any he had as a player. And it was quite a career: a batting average of .340, 493 home runs, 1,995 runs batted in and a lifetime O.P.S. of 1.080, third in major league history to Babe Ruth and Ted Williams. He had played in 2,130 consecutive games until his finale on April 30, 1939 — when he acknowledged that his once-mighty body had betrayed him with unyielding cruelty.

So he stood, wobbly enough that Manager Joe McCarthy worried he might fall, in the summer heat between games of a doubleheader between the Yankees and Washington Senators.

Gehrig looked lonely, even desolate, a solo figure on the infield, surrounded by retired teammates from the 1927 Yankees and members of the current team who had carried on brilliantly without him, with Babe Dahlgren now at first base. They were 51-17, on their way to a 106-45 record and a sweep of the Cincinnati Reds in the World Series.

It was Joe DiMaggio’s team now.

For about an hour, though, the focus returned to the star of Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day. Gifts were presented. Speeches were made by McCarthy; the mayor of New York, Fiorello LaGuardia; and Postmaster General James Farley.

All the while, Gehrig waited, the guest of honor at a living funeral.

After some encouraging words whispered by McCarthy, who adored Gehrig, Lou reluctantly stepped to the microphones.

When that moment was described by the screenwriters Herman Mankiewicz and Jo Swerling nearly three years later in their script for “The Pride of the Yankees,” they wrote: “The roar of the crowd is like a sustained note from a mighty organ. Lou waits for it to subside but it doesn’t. For him, this is crucifixion as well as triumph, because he knows he’ll have to die twice and perhaps the worst ordeal for him is that little death known as Goodbye.”

If Mankiewicz and Swerling’s words struck a hyperbolic chord, Gehrig’s did not. They were filled with gratitude for the people in his life: Eleanor, his parents, his mother-in-law, his Yankee managers, his roommate Bill Dickey, the New York Giants and the stadium’s groundskeepers.

Both versions of the speech, the real and imagined, raise one question: What would make a man who had received a diagnosis of a terrible disease speak only of good fortune and the people he was grateful for?

Gehrig offered some perspective later that year after he had begun working as a member of New York City’s Parole Commission. With his condition rapidly deteriorating, Gehrig put his name to a syndicated article (almost certainly ghostwritten) that explained what he felt was a lifetime of thankfulness: for his parents, for making his high school football team, for attending college, for signing with the Yankees, for Eleanor.

In words that echoed the speech, he wrote, “This summer I got a bad break. The doctors said I couldn’t play baseball. All right. I’m still the luckiest man on earth when you add things up. I’ve still got a long season of life to play out, and my team — America — is absolutely the best in the league. That’s what counts.”

That season of life was all too short. Gehrig died on June 2, 1941.”

“Richard Sandomir is the author of “The Pride of the Yankees: Lou Gehrig, Gary Cooper and the Making of A Classic.”

Richard Sandomir is an obituaries writer. He previously wrote about sports media and sports business. He is also the author of several books, including “The Pride of the Yankees: Lou Gehrig, Gary Cooper and the Making of a Classic.” @RichSandomir”

.............

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home